Grimoires are magick textbooks, usually old ones. The majority of the ones you can easily find are Judaeo-Christian, though there are some Hermetic works in the mix as well. They usually detail out some theory and then dive into implementation with spells or rituals. The spells and rituals tend to be extremely simple, but with highly complex requirements.

Grimoires are referenced constantly in occult works, even if they have looser, more metaphoric interpretations. The books of Solomon are especially well known in many occult traditions. One common theme with older grimoires is an insistence on very specific items (e.g. a feather plucked from a dove on the second full moon of the year) and procedures depending on some form of astrology. Some of the rules end up being downright obsessive.

You have to jump through many hoops for most older grimoires in order to approach a basic spell. More modern practices will reinterpret the symbolic ideas in these books in order to make a more accessible system. Works like Summoning Spirits draw on grimoires, but built it into a more modern system.

The history of grimoires is a bit tumultuous. They’re occult works, but many are fraudulent, others are overly complex or incomplete (highly esoteric), and others are just plain cryptic. There’s a value for the more well-known ones, but it’s hidden behind the murky waters of purple prose and symbolism.

History of Grimoires

There are multiple known ancient grimoires from places like Mesopotamia and Egypt. Basically, anywhere that learns writing seems to get some kind of codification of religious occultism. Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Persia, and the ancient Jews (in exile and in Israel) were all considered to be well versed in various forms of magic. There were countless grimoires before the rise of Christianity. Other regions (such as China) have similar works, but grimoires are typically thought of as occupying Western occult practices.

As Christianity came to power, the Church began to crack down on pagan practices. The conversion of the Roman Empire ended with many converts burning occult and pagan works. This was before the advent of the printing press (in the West) which meant when some works were lost, all copies were.

During medieval times, grimoires continued to exist, but they existed within the confines of Christianity. Magick was divided into “natural” magick and “demonic” (or “satanic”) magick. The natural kinds were allowed, but anything even vaguely “demonic” was seen as an affront to Christianity. The irony was the controversy led to many grimoires being circulated which dealt with both. Acceptance fed one, controversy fed the other.

The early modern period led to a rise in attention to grimoires. The printing press combined with a renewed interest in Hermeticism led to new grimoires being produced. The 15th century was marked with the Protestant Reformation and witch trials and the Kabbalah also started to spread. Rosicrucianism rose from a mixture of Kabbalah and Hermeticism.

As the Inquisition kicked up, more and more grimoires were banned. The witch hunts made anything magickal or occult strictly Satanic in nature. Works continued to be published, but various governments looked to restrict folk beliefs and occultism to try and end the witch hunt. The burden moved from the church to the community.

The 18th and 19th century saw a large growth in grimoires in circulation. Books which had been banned now weren’t, and countries like France were producing them. The church had lost influence. Wicca is known for having several modern grimoires, but other systems have them as well.

Magickal Textbooks

Grimoires are often viewed as magickal textbooks. They lay out a system and apply it in a given system of magic. How well this works depends on the grimoire and the ideas behind it. Like I mentioned before, some have another system which helps interpret them.

If you view magick in a more modern sense, most grimoires are a system of recipes which can easily be adapted to similar, but different ingredients. If you can’t get panko, cornmeal or bread crumbs might work instead. You have to understand what you’re making and why an ingredient is used to make a substition though.

Most grimoires have extremely difficult to acquire ingredients. But, if you look at most occult systems, they focus on concentrated energy and effort to get results. The effort you expend getting a virgin dove feather can be taken as symbolic for a stronger invocation or other shortcut with the right interpretation.

Grimoires remain popular because they promise a recipe to success, but it tends to be cryptic. Did a spell fail because you couldn’t get a virgin dove feather on the second Tuesday of a month or because you didn’t maintain the right attitude? This provides an out, but also an abstraction. A long division lesson teaches a method which can be discarded once you understand how and why division works in general, but it’s hard to make the jump without the lighter cognitive jump.

Judaeo-Christian Grimoires

For most older works, you’ll only find Judaeo-Christian grimoires. The Christian Church ended up censoring many of these works via various inquisitions and movements. Some works such as the Key of Solomon were revitalized, but they at least started with a more Semitic religious outlook. Other works were not so lucky.

Due to polarization from the church, most works will be some kind of demonic control or else a natural grimoire, fitting into the two categories neatly. You have works like The True Black Magic which feels like a variant of Solomonic magick, but there are countless works which fit in either category. As the church lost power, more and more grimoires surfaced. Nations like Switzerland weren’t under the thumb of the church and became occult hubs.

Despite the fact that laws varied, keeping everything in a relevant Judaeo-Christian friendly framework just made sense. It was a lot harder to get punished if the work accepted and propagated Christian beliefs or at least referenced the bible. It wasn’t until the more modern period that we got grimoires which weren’t either Judaeo-Christian, or at least largely tolerated by the church (Hermeticism).

Usefulness

Grimoires are often overlooked for more modern occult practitioners. Though the systems are old and often unreliable unadjusted, more modern occult practices can make older grimoires come to life. The Book of Solomon’s Magick is one such book which takes a modern approach to older methods. The older grimoires hold some value, but not really much without an ability to interpret the ideas behind them.

To top this off, there are countless fraudulent grimoires on the market. While if you believe that the belief gives it power, these can still be useful, most fraudulent ones are just rambling nonsense. The being said, I wouldn’t mind another copy of the Necronomicon just because it’s fascinating (and not expensive). It isn’t useful as a self-contained system, but what of value is embedded in it?

This is the much harder question to answer. Most of the Solomonic magick has some kind of adoption into other traditions. Newer fictional works such as the Necronomicon can be used in some way, but really aren’t rooted in a real occult tradition. This doesn’t mean the work is useless though if you approach the occult as something based on energy work or similar. Are you performing magick by following rigid guides, or is the ceremonial intent enough?

How you answer this question affects how useful a griomoire is. While most are going to be relatively useless in a self-contained fashion, many of the rituals or concepts can be adopted in modern practice. I may not put much faith in most of the grimoires I own, but they’re not going anywhere either. Even if they seem useless to you, they are at least extremely interesting to read if you’re into spirituality or the occult.

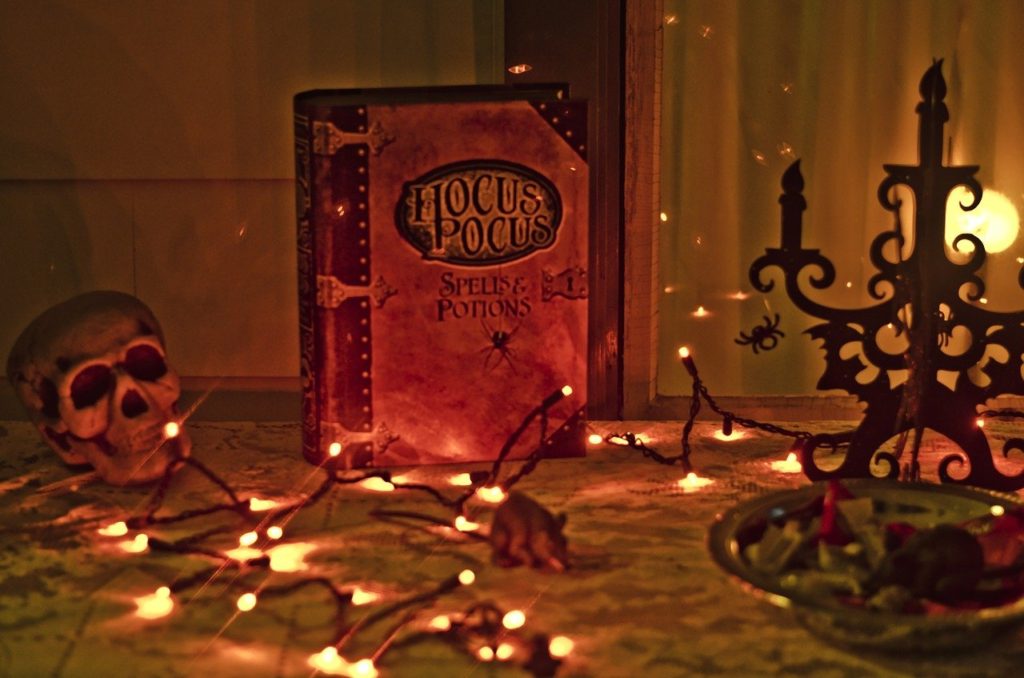

Image by RachelBostwick from Pixabay

Fantastic blog. Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool. Jeannette Ermin Benedix

Great delivery. Sound arguments. Keep up the good effort. Kelci Jerrie Knitter